By Gloria Dickie and Allison Lampert

MONTREAL (Reuters) -As countries prepare to negotiate a new global agreement to protect Earth’s environment, the head of the United Nations warned there was no time to lose.

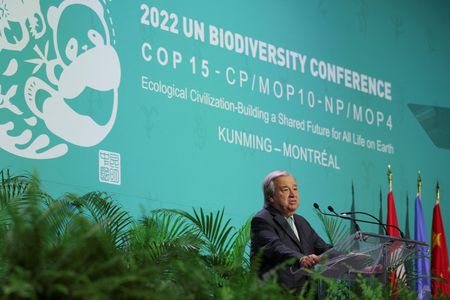

“Humanity has become a weapon of mass extinction,” U.N. Secretary-General Antonio Guterres told delegates to the COP15 biodiversity summit at an opening ceremony on Tuesday in Montreal.

“This conference is our chance to stop this orgy of destruction,” he said.

More than 1 million species, especially insects, are now threatened with extinction, vanishing at a rate not seen in 10 million years. As much as 40% of Earth’s land surfaces are considered degraded, according to a 2022 U.N. Global Land Outlook assessment.

Negotiators hope that the two-week U.N. summit yields a deal that ensures there is more “nature” — animals, plants, and healthy ecosystems — in 2030 than what exists now. But how that progress is pursued and measured will need to be agreed by all 196 governments under the U.N. Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD).

Ahead of the talks beginning in earnest on Wednesday, observers warned that the process was already looking like a struggle. Three days of pre-summit talks that ended Monday failed to deliver a clean draft agreement for negotiation ahead of the summit’s close on Dec. 19.

“Some progress has been made, but not so much as needed or expected,” CBD executive secretary Elizabeth Maruma Mrema told a news conference Tuesday. “I don’t feel the delegates went as far as we had expected.”

More than 10,000 participants, including government officials, scientists and activists, are attending the summit amid calls by environmentalists and businesses to both protect natural resources and halt the loss of species.

Canadian Prime Minister Justin Trudeau stressed the need for countries to protect 30% of their land and waters by 2030 – a key request of the United Nations. He also said Canada would put $350 million toward international biodiversity finance.

“There are lots of disagreements between governments,” Trudeau said. “But if we can’t agree as a world on something as fundamental as protecting nature, then nothing else matters.”

STICKING POINTS

The U.N. biodiversity talks, held every two years, have never garnered the same attention as the world’s main environmental focus – the annual U.N. talks on climate change. But there is increasing awareness that protecting nature and controlling climate change go hand-in-hand.

Healthy ecosystems such as forests and seagrass beds are key to controlling global warming. At the same time, rising global temperatures are increasingly threatening many ecosystems as well as species unable to adapt quickly or to move to cooler climes.

Overall, the U.N. hopes to persuade all countries to pledge to put at least 30% of their land and sea areas under conservation by 2030 – a target often referred to as the “30-by-30” goal. Currently, only about 17% of the world’s land area falls under some sort of protection, while less than 8% of the global ocean is protected.

Another 22 potential targets are also being considered, from curbing pesticide use to canceling some $500 billion in subsidies for activities that cause damage to nature.

But the draft deal is still riddled with bracketed phrases – indicating a lack of agreement, negotiators said. While previous iterations of the agreement had about 900 brackets, that number ballooned up to about 1,400 during the discussion in the days ahead of COP15.

Some of the toughest areas include whether to include efforts to curb climate-warming emissions, whether to impose a deadline for phasing out pesticides, and how to ensure poor nations will have the funding needed to restore degraded areas.

Even the 30-by-30 goal gets tricky in the details, given that some nations hold vast land or ocean areas teeming with wildlife, while others do not. Some indigenous groups have also pushed against the goal, which they see as potentially threatening their land rights.

Indigenous protesters and allies disrupted Trudeau’s speech on Tuesday, beating drums and unfurling a banner that read “Indigenous genocide = ecocide. To save biodiversity, stop invading our lands.”

Trudeau is one of the only world leaders expected to attend the summit. Negotiators have said that the absence of most world leaders could make it tougher to reach an ambitious agreement.

China was due to hold the summit in the city of Kunming but postponed the event four times from its original date in 2020 due to COVID before agreeing to hold the talks in Montreal.

Montreal police have put up a 3-meter (10-foot) fence around the downtown summit venue, Palais des congres, and are preparing for thousands of student protesters expected to swarm the Montreal’s streets to demand a strong deal to protect nature.

(Reporting by Gloria Dickie; Additional reporting by Jake Spring in Sao Paulo and Simon Jessop in London; Editing by Katy Daigle and Lisa Shumaker)